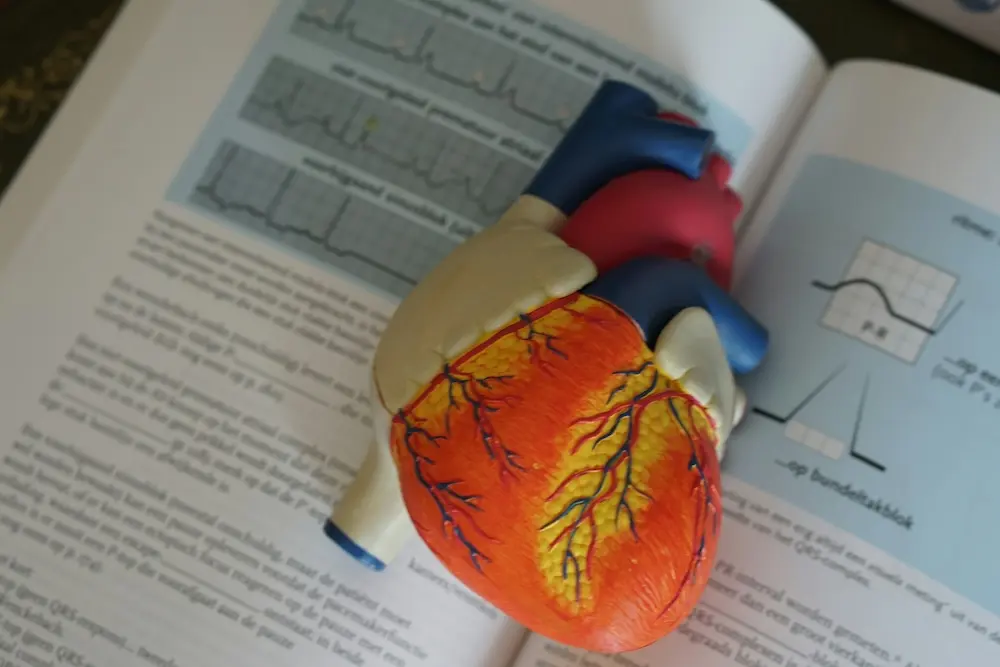

We have said more than once that cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide; that is why it is so important to keep the health of this body system under control. Today we will analyze in more detail what the cardiovascular system is and why the groups of diseases associated with it are the greatest threat. And this is not only because it passes through the entire body, as seen in the picture.

Understanding the Cardiovascular System and Its Functions

First of all, note that this system consists of several essential parts, which together allow:

- “Carry” oxygen, fats, vitamins, carbohydrates, and other substances necessary for functioning to all organs and take the products of their vital activity;

- They move blood around the human body and maintain constant and stable functioning of all systems (in other words, they participate in homeostasis). This function also regulates body temperature

- Protect the human body from exposure to harmful microorganisms and substances – deliver special cells (lymphocytes) to any damaged area.

The crucial parts of the cardiovascular system are the heart and blood vessels. All organs and systems of the body integrate through their fully interconnected work, and the body transports nutrients necessary for life to each of its parts. Metaphorically, we can imagine the Cardiovascular system as an ideal life support system: the “food” will bring, and the “garbage” will take out, and the own system will check the status, and if necessary, it “call the doctor.” The cardiovascular system remains closed, in contrast to even the most perfect “delivery” system. This means that all the components are related, and the blood does not go beyond its limits.

Uninterrupted supply of oxygen to organs and tissues and maintenance of gas exchange in the lungs, provide two circulatory circuits. Both begin and end at the same point – in the heart. The large circuit is responsible for the supply of nutrients to all tissues and organs, the small one, also known as the “lung,” for the nutrition of the heart, and the exchange of carbon dioxide again for oxygen. At the same time, since the heart is our main motor, we will stop to describe in more detail this organ.

The Heart: The Engine of the Cardiovascular System

The engine of our life’s progress is located in the chest cavity, approximately ⅔ shifted to the left side and it certainly looks like this:

The heart is a very independent organ; it can contract due to the impulses that arise in it, but we will explain this later. So, to begin with, we note that on the right model it is clearly visible – the heart is hollow. A continuous septum divides this cavity longitudinally into 4 chambers: the right and left atria and the right and left ventricles. People sometimes refer to the left atrium and ventricle as the “arterial heart,” while they call the right atrium and ventricle the “venous heart.” Of course, like any vital engine, the heart has its own protective body – the pericardium, also known as the circumferential bag, which fixes the organ in a specific position in the body. The fluid released between the layers of the pericardium reduces the friction between the wall of the heart and the tissues of other organs, prevents overstretching of the heart muscle and overfilling of the organ with blood, and also protects it from mechanical damage.

Of the following names, endocardium, myocardium and epicardium, you have probably heard the second, against the background of “myocardial infarction.” It sounds unusual, but in fact, it’s simple. These are the three layers of the heart wall:

- Internal (endocardium), which forms the surface of the heart chambers and prevents excessive friction when blood passes through the heart;

- Middle (myocardium), the most voluminous layer of muscle tissue. The more work the heart does, the stronger the myocardium develops. Connective tissue separates the middle layer of the atrial myocardium from the ventricular myocardium, causing these parts of the heart to contract alternately rather than simultaneously;

- The external layer (epicardium) forms a special outer shell consisting of connective and epithelial tissue.

Between the atria and ventricles, there are special flap valves. The blood enters the ventricles, then, when the pressure in them increases, it lifts the valve flaps, and goes to the atria, after which these leaves close, interrupting this process until a new increase in pressure in the ventricles. And no, the door effect in the Wild West saloon will not work here: these doors do not turn out in the opposite direction due to stretched tendon threads.

Valves also exist between the ventricles and the vessels. Doctors call these valves semilunar. They no longer look like leaves, but pockets: when the ventricles relax, blood fills the space of the valves, and their walls close, blocking the vessel’s lumen and not letting any more blood into the ventricles. As blood leaves the ventricles, it presses the valves against the vessel walls, opening the inlet for a new cycle.

Thanks to the valve system, the blood moves in one direction: veins →atria → ventricles → arteries. In simple words, the heart’s main function is to pump blood. This happens in several stages:

- Blood flows through the veins to the atria.

- The atria contract (systole), the swing valves open, blood enters the ventricles. This phase takes approximately 0.1 seconds.

- The ventricles contract (systole), the semilunar valves open, blood enters the arteries. This phase lasts 0.3 seconds.

- The atria and ventricles relax (diastole), the semilunar valves close (so that blood from the arteries cannot enter the ventricles). Diastole takes 0.4 seconds.

At an average rate of about 75 beats per minute, the heart completes one full cardiac cycle in 0.8 seconds. During one such cycle, 70 ml of blood enters the aorta normally, and the heart can pump 7-10 thousand liters daily.

The Journey of Blood: How Vessels Ensure Circulation and Metabolism in the Body

An important component of the cardiovascular system are blood vessels. Anatomists traditionally divide blood vessels into three types: arteries, capillaries, and veins. Each type performs its own function.

- Along the arteries, blood saturated with oxygen and other substances moves from the heart, and directly from the main artery of the system that is the largest of them – the aorta.

- Next, the process flows into the capillaries, the smallest vessels, and through their walls, metabolism occurs between blood and tissues. At this stage, the blood releases oxygen and becomes saturated with carbon dioxide and other “waste.”

- Then, blood carrying substances that the body needs to remove enters the veins and returns to the heart through them.

- The heart pumps this blood to the lungs, where it releases carbon dioxide and absorbs oxygen..

- Then, the newly enriched blood from the lungs, with the help of pulmonary veins, goes to the left atrium, through it – to the left ventricle and aorta, and again the circulatory cycle begins.

In their structure, blood vessels are similar. The arteries have the thickest walls with three membranes (by analogy with the walls of the heart and here there is an internal, middle and external one). Moreover, the further the artery is from the heart, the smaller its size.

Veins have a similar arrangement to arteries, but with some differences: they have thinner walls and less elastic and muscle tissue. And, finally, capillaries, the thinnest of all blood vessels: it is because of the small walls that they are able to perform the metabolic function.

In general, the walls of blood vessels are an elastic structure capable, depending on the blood pressure, of narrowing or, conversely, stretching. The muscles inside the vessel walls maintain constant tone to ensure uninterrupted blood flow. This constant tension, combined with the heart rate and its strength, maintains the necessary blood pressure for unhindered access to every organ and tissue in the human body.

The Role of Lymphatic Vessels in the Cardiovascular System

The lymphatic system participates in metabolism and removes “excess” substances from the body’s tissues and cells. However, it complements the cardiovascular system rather than being an immediate part of it. Earlier, we talked about the fact that the blood removes harmful substances through the veins – this is not the only way that the fluid still leaves the organs in the form of lymph, already through the lymphatic vessels. However, don’t think of these as two parallel systems. Lymphatic vessels connect to blood vessels from muscles and many organs, and their contents flow together. In addition, closer to the heart, the flow of blood and lymph merge into one. The vessels of the lymphatic system have three-layered walls and contain valves that direct lymph movement toward the center of the body.

The features of this type of vessel are mainly related to their location in the human body:

- Deep lymphatic vessels are those that come out directly from the tissues of internal organs.

- The superficial ones are located near the subcutaneous veins and are smaller than the first ones.

In addition, unlike their closest neighbors, blood vessels and lymphatics do not reach many areas of the body, whereas blood permeates all areas due to capillaries. Among such exceptions are the cover of the eyeball, the lens, the epithelium of the mucous membranes, the outer layer of the skin, etc.

The lymphatic system differs from the cardiovascular system in key ways: it absorbs water from tissues and removes waste products from cells. However, its main function is protection. The lymphatic system traps dust, smoke particles, dead cell debris, bacteria, microbes, and foreign particles. Additionally, lymph nodes produce plasma cells capable of generating antibodies and certain types of lymphocytes that help form immunity.

So why are cardiovascular diseases so dangerous?

The information above demonstrates that the cardiovascular system’s expansive structure encompasses the entire human body. If stretched into a straight line, an average adult’s cardiovascular system would extend about 100,000 kilometers. And because of the system, firstly, it is necessary for organs and tissues to get oxygen and other nutrients. Secondly, a severe and closed “rupture” at any site can hinder the whole body’s functioning. Moreover, the “enemies” of this system are not only “natural”: in addition to various diseases that can arise regardless of lifestyle, there are also dangerous factors for which we ourselves are responsible.

Therefore, in the absence of physical exertion and a sedentary lifestyle, even with a slight increase in the activity (conditionally, had to walk up the stairs due to a lift broken), there are palpitations, shortness of breath, and other: signs sure that the heart has to pump several times more blood to supply the body with the necessary level of “fuel.” When a person neglects physical activity for a long time, their heart becomes unaccustomed to heavy loads. In such cases, merely increasing the heart rate fails to adequately “nourish” the body. Moreover, the heart muscle develops weakly and tires quickly. After sudden exertion, it may temporarily worsen blood circulation. But the “sports” heart is good only for professional athletes – everything needs balance. And we have not yet addressed the problems of stress and excessive mental loads.

Understanding how your cardiovascular system functions is key to preventing serious health issues. If you’re concerned about your blood pressure, learn more in our next article on hypertension, high blood pressure: causes and symptoms.